One evening, my friend Terry Talley – a stage actor, a playwright, a manager of charitable donations at UNICEF, a white guy, and an often infuriating but always true-hearted good person – arrived at his unassuming apartment building on Manhattan’s Upper West Side to find two black men standing by the elevator in the entrance hall. Encountering two black men he had not seen before in the lobby at night set off wiggly hairs on the back of Terry’s neck. (A response familiar to you?) He later told me that his initial impulse was to act like he had just remembered something, turn quickly and go back out the door onto the street. Instead, he told himself something like, No. I do not want to be a racial profiler. That’s not who I am. Terry did not turn and leave but waited with the men for the elevator. What happened next leaves, perhaps, no lesson to be learned or, perhaps, a piece of one of the greatest lessons we could ever learn, like: who we are and/or who we want to be. In any case, it leaves high-octane fuel for the ongoing conversation on race in America.

Let me interrupt this story to say that it took place back in the 1990s.

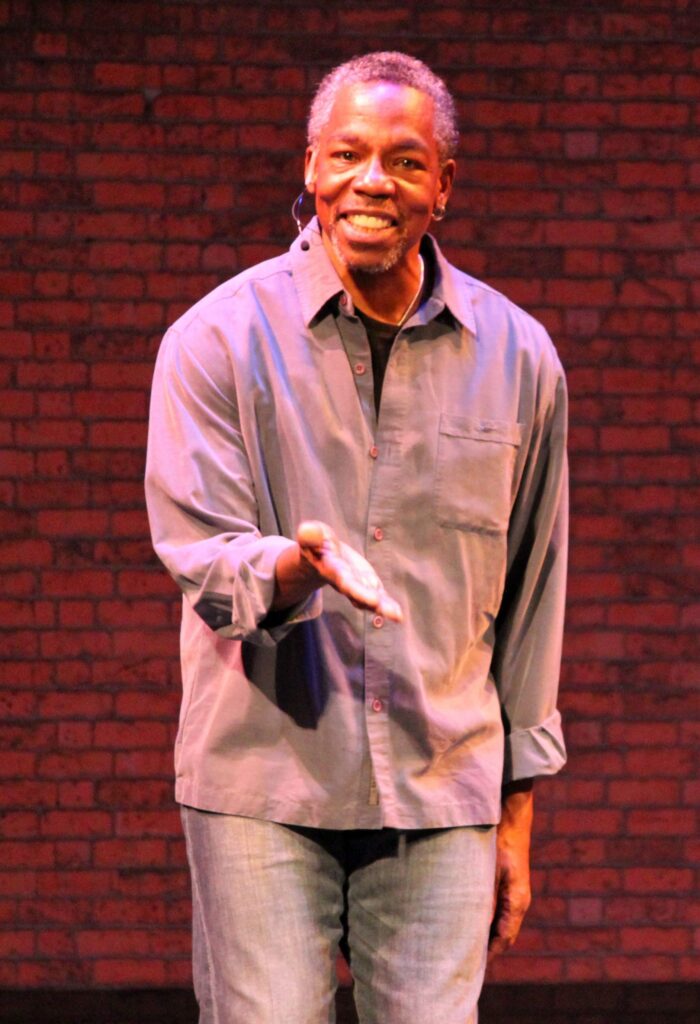

Fast forward for a few moments to 2013 when actor LeLand Gantt – in developing his solo examination of race in America, Rhapsody in Black – said, “I just want to start a conversation.” Since then, there has been a lot of talk.

Rhapsody in Black is a one-person show. It is the chronicle of LeLand Gantt’s own personal – though by no means atypical – black man’s journey through the often camouflaged, sometimes undisguised, always variegated aspects of racism in America. It began as a showcase at the Actors Studio. While the piercing, unflinching, and often funny piece on bewilderment, anger and transcendence is written and performed by Gantt, it was directed by – prepare for it… – Estelle Parsons: Academy Award-winning Best Supporting Actress (1967) for the groundbreaker Bonnie and Clyde, and Rosanne’s mother on the sitcom Rosanne. In interviews (2015) for Carousel newspaper, Parsons told me that she calls herself Rhapsody in Black’s, “Directorial Consultant.”

Gantt expounds, “She has such incredible sight into the human condition, there was never a moment where I felt that I could not speak to her about ANYTHING in or around or about myself. I couldn’t ask for a better squire for my show – whether she calls herself a director or not.”

Gantt’s onscreen acting credits include small supporting roles in films such as Requiem for a Dream and Malcolm X, dating all the way back to Presumed Innocent (1990), and television guest appearances on such current series as Law & Order SVU, and The Good Fight. His onstage performances of Rhapsody… toured the eastern United States (with stopovers in Sweden and Ontario, Canada) for about four years. The show included talkback sessions following each performance in which audiences could interact regarding what they had just witnessed – affirming, questioning, challenging their responses to the live experience they had just shared.

The physical tour was halted by the COVID pandemic. Rhapsody… evolved into a streaming event commissioned by various venues, organizations, and institutions. Viewers can now access the piece in three versions. There is a full 90-minute recorded performance; there is a 60-minute rendition appropriate for adolescent audiences, without any of the sexual stuff; and there is an Asynchronous Segmented edition divided into three movements for ease of classroom viewing and discussion.

Back in March of this year, saboteurs attacked the livestream talkback session following a Rhapsody… presentation through the public high school in East Greenwich, Rhode Island – cutting off Wi-Fi to some of the participants and spattering the chat with what the local newspaper reported as, “offensive comments which included profanities, and at least a couple of uses of the n-word…” That is, of course, how evocative the conversation on race can be. In this challenge we face as a society, responses are triggered; we could converse about what is triggered by the story of what happened to Terry Talley.

The elevator arrived at the lobby, the three men entered it and the door closed. When the door slid open on Terry’s floor, he was being held at gunpoint. The strangers walked him down the hall and forced him to admit them into his modest apartment where they bound him. They then proceeded to seize any objects they could find of any value – some practical, some beloved, and all financially and/or emotionally difficult or impossible to replace.

When Terry died many years later, I told that story at his memorial service. I recall framing the incident somewhat humorously. I used the sardonic phrase, “of course” just before relating that the men pulled out a gun in the elevator. Shame on me?

LeLand Gantt confessed to me in those 2015 interviews that racial profiling, “is so pervasive a construct in our society…that, even as a victim of it, I myself sometimes perpetrate it. I actually have found myself impelled to react defensively to the fact of approaching a few young black men on the street at night – just because they are black.” If Terry Talley had followed his initial impulse and left the building, would he have been racist? If the men had been white, would he have had the same instinct?

“There are times when common sense would lead you to ‘cross the street,’ physically or metaphorically, to protect yourself when on a dark street in a shady neighborhood at night,” LeLand proffered. “But this situation isn’t in vogue ALL THE TIME.”

If Terry had left the building, he would have been spared the dual traumas of being threatened with a gun and bound, and he would not have been robbed of the property, and the experiences he might have continued to enjoy with the property, that the thieves stole from him. But would that choice have robbed him of something more precious?

“The clutching of the purse, crossing of the street in broad daylight to evade proximity to that idly-approaching-not-threatening-you-in-any-manner-other-than-just-being-black person, and the assumption that that person is more likely to be a criminal or dangerous to you simply because they are black needs to be examined,” Gantt suggests. “If one can do that, NOW we have a conversation!”

For more information on viewing or commissioning Rhapsody in Black get in touch at www.rhapsodyinblack.org/contact.

~ FW